Al-Nikhaila Mosque: Historical Antiquity Shining Once Again

By: Sabah al-Taliqani

The town of al-Kifl lies around 30 kilometres south of al-Hilla and 130 kilometres south of Baghdad, in the middle of a fertile plain through which the River Euphrates runs, beautifying the town and watering its farmland. The town's name derives from the Islamic prophet Dhul-Kifl, frequently identified with the Judeo-Christian prophet Ezekiel, whose shrine is situated by the town’s historic al-Nikhaila Mosque.

Hussein Revivalism spoke to Wisam Lateef Safi, the deputy secretary of the Shrine of Dhul-Kifl, about the mosque. He told us that the mosque's history goes back to the time of Imam Ali, the Commander of the Faithful, and it was in this place that he prayed before heading out to face Muawiyah at the Battle of Siffeen, and again before fighting the Kharijite rebels at the Battle of Nahrawan. Soon after, the al-Nikhaila Mosque was built upon the site of Imam Ali's prayers. The historians record that the mosque's stone pulpit was erected by Sayyid Taj al-Deen al-Aftasy before his death in 171 ah.

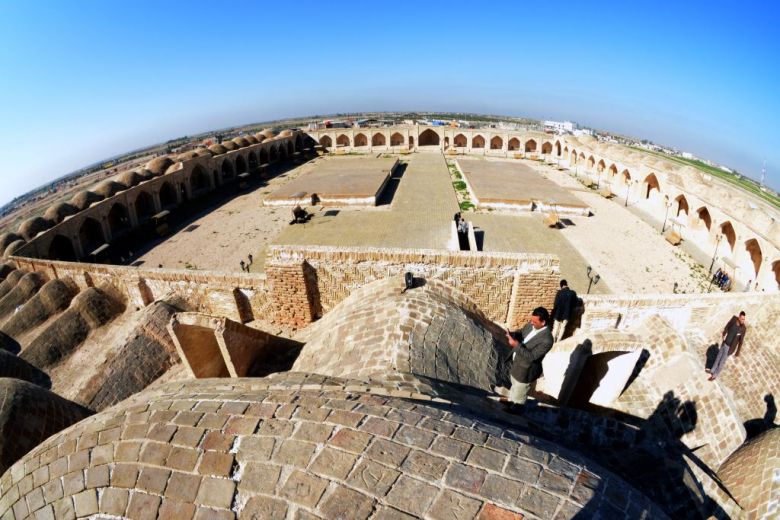

Safi brought the story forward to the reign of the Mongolian Ilkhanid ruler Muhammad Khodabanda around 703–716 ah. Though Khodabanda was from a Mongolian dynasty that had conquered the area around Baghdad, he had converted to Shi‘ah Islam through the prominent Shi‘ah scholar Allamah al-Hilli. Khodabanda renovated the al-Nikhaila Mosque and the Shrine of Dhul-Kifl. The mosque's walls date back more than 700 years to around this time and measure 1.35 metres in width, 3 metres in depth, 9 metres in height, and 663 metres in circumference.

However, the holy niche (mihrab) where Imam ʿAli prayed before the Battle of Siffeen, which once lay on the left entrance of the Shrine of Dhul-Kifl, was tragically removed by extremists in 1860 ad.

The desecration of the mosque did not end there; more recently all but three of the mosque's towers were buried under residential building projects in the vicinity. Sheikh Hazim al-Ameri, the imam of Imam Ali Mosque in al-Kifl, told us how under the last dictatorship the mosque, known at the time as Khan Kreish, was closed for worship and relegated to a storehouse for various items, and people began to forget that Khan Kreish was a monument of great historical and sacred importance.

However this religious repression was ended after the fall of the dictatorial regime in 2003. The return of religious freedom allowed the residents of al-Kifl to re-explore the al-Nikhaila Mosque and rediscover its value. Sheikh al-Ameri recalls how they began a cleaning campaign that was participated in by numerous residents of the area, which began by removing all the inappropriate items stored inside the mosque. He told us how the first step in restoring the holiness of this site was to hold Friday prayers inside the holy shrine of the prophet, and with blessings from the prayer they were able to highlight the sanctity of the site.

The situation was then discussed in the offices of the religious authorities after Sayyid Riyadh al-Hakim, in collaboration with an archaeologist from the University of Kufa, Dr Khalid al-Musawi, first visited the site in 2003 and clarified the historical value of the matter. Dr al-Musawi mapped the plans and dimensions of the site and explained all the acoustic and visual aspects of the mosque.

A fence has been put up around the mosque to protect it from vandalism. The mosque’s walls and minaret are still in very poor condition and require urgent repair and reconstruction, but there is hope that these will be completed quickly now the matter has been taken to the offices of the President and the Prime Minister.

A well was discovered in 2009, situated south of the minaret and connected with the old wall of the mosque. A second section was discovered using radar technology, owing to the difficulty of excavating a site now underneath a residential area.

In regards to the details of the mosque, Safi stated that the mosque's walls and minaret carry numerous Islamic decorations and inscriptions that combine geometric, vegetal, and Kufic scripts, all of which were inspired by local Iraqi elements that were common before the Mongol invasion of Iraq. The most wonderful of these formations is located in the middle of the hull of the Minaret and consists of rare Kufic writing on overlapping triangles that reads ‘I love Muḥammad and Ali’.